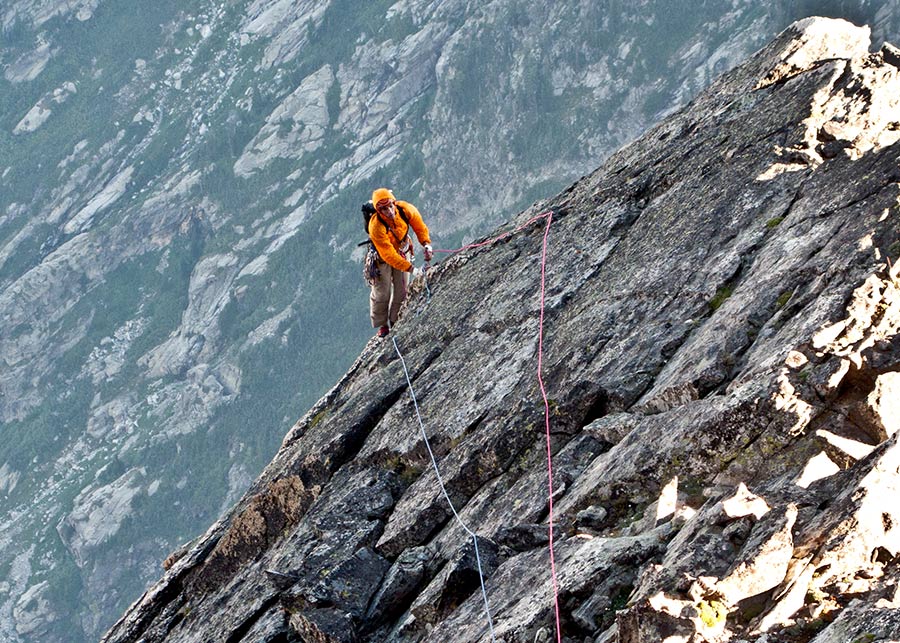

Adam Riser has spent the last 20+ years rock climbing, ice climbing, mountain biking, and backcountry skiing. He has worked as a river guide in the Pacific Northwest as a climbing guide on Mt. Rainier and as a writer and photographer in the outdoor industry for over a decade. His words and photos have appeared in industry magazines, websites, and catalogs including Gripped, Black Diamond, CAMP, backcountry.com, Cotopaxi, Safariland, and others.

Adam Riser has spent the last 20+ years rock climbing, ice climbing, mountain biking, and backcountry skiing. He has worked as a river guide in the Pacific Northwest as a climbing guide on Mt. Rainier and as a writer and photographer in the outdoor industry for over a decade. His words and photos have appeared in industry magazines, websites, and catalogs including Gripped, Black Diamond, CAMP, backcountry.com, Cotopaxi, Safariland, and others.

Adam now lives in Salt Lake City, Utah for its access to world-class climbing, mountain biking, skiing, and an international airport. In addition to climbing throughout the states, Adam has been on expeditions to Alaska, the Canadian Rockies, the Northwest Territories, and Peru.