The Rascal continued to hold strong, and around 1 AM Autumn started the motor to steer into the wind and minimize the amount of strain on the anchors. At approximately 2 AM, someone in the marina reported winds up to 108 miles per hour.

These are Autumn’s words describing conditions on the Rascal during the storm:

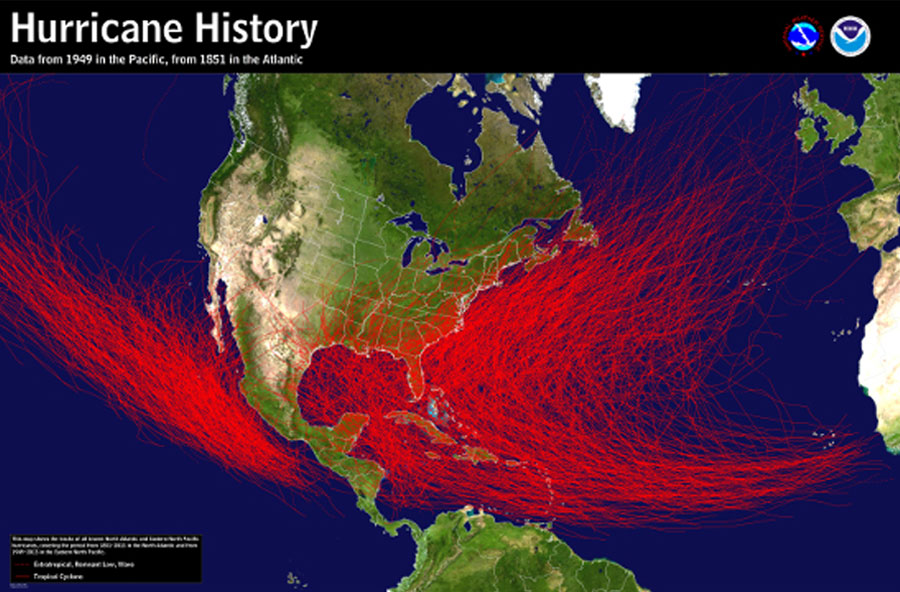

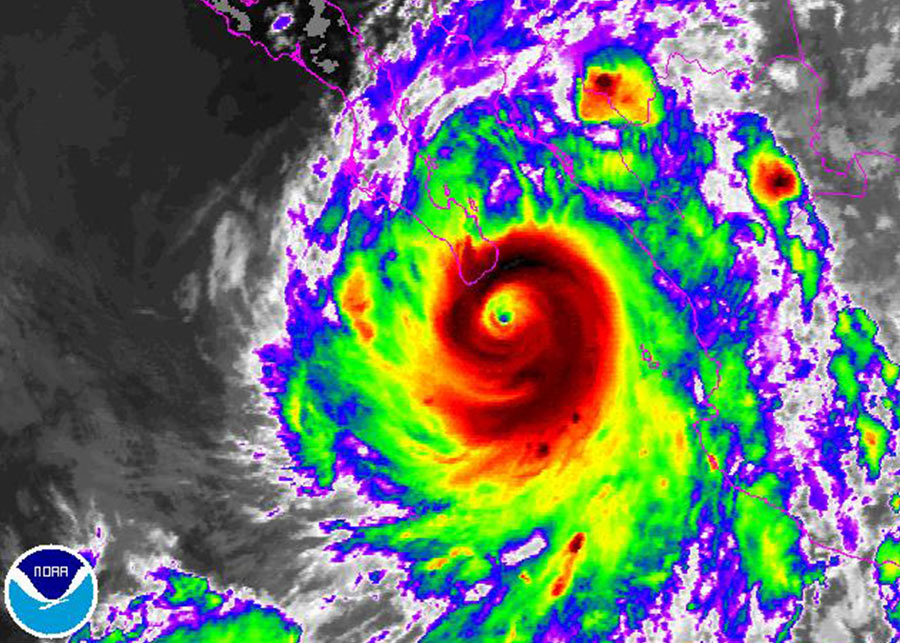

On a previous voyage across the Gulf of Mexico, I had experienced a burly tropical depression with sustained winds at 50 knots, however Odile was like nothing I have ever experienced. Cruisers anchored in the bay discussed that the storm would pose a particular challenge because it would pass over us in the depths of night making visibility impossible.

Throughout the night, cruisers with weather stations reported the increasing wind speeds—45, 58, 67, 75, 108, and eventually 125 knots. There wasn’t much rain until around midnight, which coincided with a much larger increase in wind speed. In preparation for the storm, I had stripped Rascal of all her sails and tied all the halyards down to reduce windage, noise, and chaffing with the rigging, which proved fortunate as the howl of the wind and rain literally sounded like a jet plane.

I turned the VHF radio volume up to high in order to hear transmissions over the roar. Calls and alerts from surrounding boats were already coming in early in the night. A good friend, Gunther, called over the radio that he had hit something and was concerned that he was adrift. In his late seventies, Gunther and I had become quick friends over the prior weeks, sharing roasted chickens and tales—he was an incredible storyteller. No one returned his call. I hailed him immediately knowing that the most I could offer was an open ear and perhaps a problem-solving discussion of what to do next. We decided he should throw out his second anchor, which he did. The distress I heard in his voice is something I will never forget. It was the last time I spoke to Gunther.

Through the port windows and white-out rains, I could just barely see the silhouette of boats anchored near me. One by one, they broke free of their anchor and sailed past into the darkness until there were no boats around me that I could see. As each one let loose, my adrenaline pumped a bit, and I would give the Rascal a pat as I perched in the companionway.

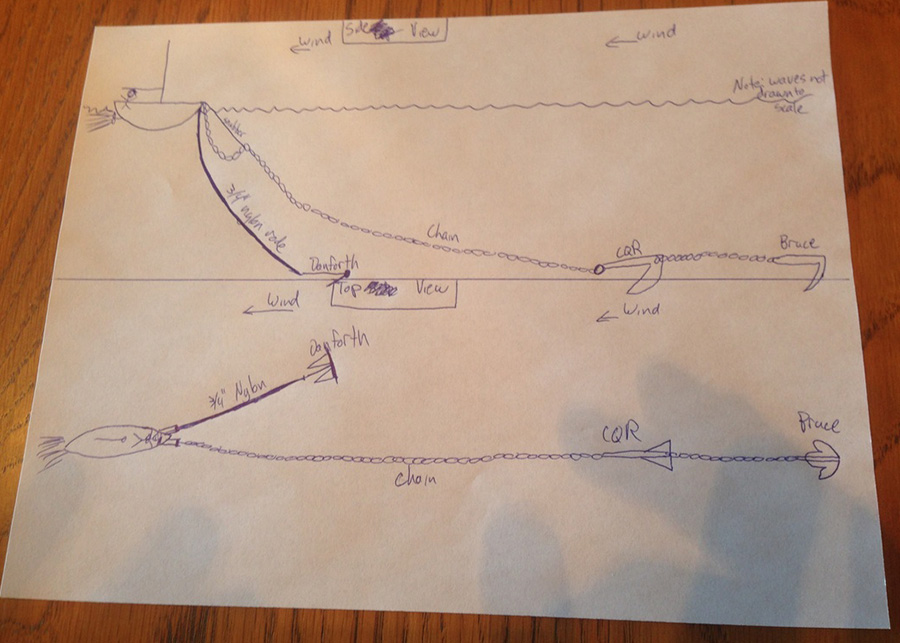

The Rascal was rocked by 8-10 foot waves, and I kept my ear tuned to any noise that might mean something was awry on the boat or with the anchoring. Indeed, as the winds picked up to ~ 75 knots, I heard a distinct rubbing and grinding toward the bow. Many cruisers had told me to wear a snorkel mask in order to be able to see and breathe in the driving rains that would come. They were exactly right. With headlamp, life jacket, harness, and snorkel mask on, I crawled from the cockpit to the bow as the Rascal bucked in the waves and the rain pelted me like gravel.

At the bow, I found the chain and snubber had come free of the bow roller and were chafing against the roller’s edge—the snubber being slowly chewed. With every wave, I held the pulpit as the Rascal’s bow dove into the water, and I got a salty dunk. The tension against the snubber and chain released a bit in the wave troughs, and I was somehow able to lift them both back into the bow roller without crushing my fingers. I would go out on deck several times over the course of the night to check the snubber, chain, and windlass, and each time the wind and waves had increased as the eye moved closer.

Autumn continued monitoring her position on the GPS, ensuring lines all looked good on the bow. At 2:22 AM she texted, “Loud noises!”.

At first, I thought she was quoting the movie Anchorman, which I didn’t find funny. It soon became clear that something on the boat had failed and was making loud noises up on the bow.

The pull from the Rascal stretched the snubber so much that the chain was taking the tension. I had tied the bitter end of the chain to an exceptionally strong cleat on the boat’s deck with a ⅝-inch dock line. I never expected it to come tight, but I thought this beefy dock line could hold the strain if it did. It apparently could not, and the parting of the dock line (and the chain’s escape) caused the loud noises Autumn heard.

The snubber, however, was still attached to the chain, and it stretched an incredible amount, holding the boat for about another 5 minutes before it finally parted.